A new technical and commercial comparison of alternative fuels for ocean carriers compares expected bunker costs for different size and differently equipped ships. Alphaliner, a consultancy for ocean carriers, has reviewed that comparison.

Alphaliner’s review shows the ship owner and operator what they can expect in economy over the next few years. The results indicate that as the new regulations for CO2 emissions kick in, fuel costs will become a much larger percentage of total ship operating costs, perhaps double, or even more.

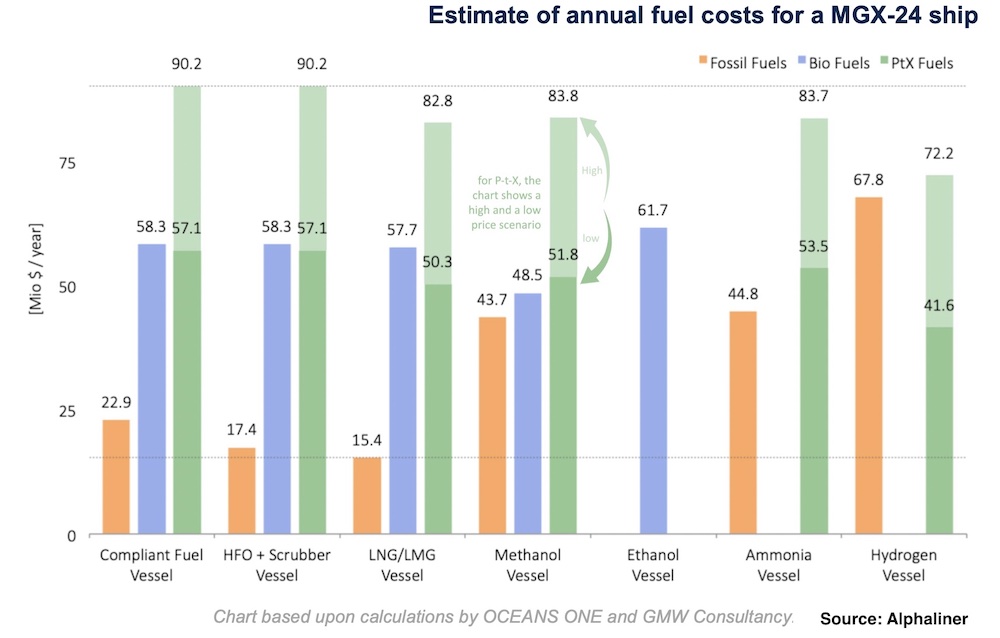

For instance, the graph they publish shows fuel costs for differently equipped Megamax-24 (MGX-24) ships. A megamax-24 ship is typically 400 meters long and 61 meters wide, with a depth of about 33.2 meters. It should carry around 23,500 twenty-foot equivalent (TEU) containers (Alphaliner newsletter).

The graph compares use of fossil fuels, bio fuels, and power-to-fuel (PtX) fuels (read about them). The PtX fuels convert renewable sources such as wind, sun, hydro, and geothermal, to fuel products such as hydrogen, ammonia, or products containing carbon, such as syn-crude. If carbon is used in the PtX process it should be from non-fossil sources or unavoidable industrial carbon emissions capture and reuse.

Even bio-fuels cost a lot more than conventional fuels when all the upstream supply chain emissions are considered, for these very large ships.

The graph seems to imply that scrubbers are still a very important technology in the fight to clear the air. And LNG has a role to play, though it might be temporary. At their best, the PtX technologies such as electric-powered ships are comparable to or better than bio-fueled vessels.

There’s clearly a long way to go for ocean shipping to go where it needs to in the race to clean up global emissions.

However, some of these non-fossil technologies will adapt over the next few years, and costs will come down. It’s hard to do much more with the fossil fuel technology.

The argument Alphaliner makes is that soon fixed costs will be a smaller part of the total cost of a large ship than fuel operating costs. As these proportions change, emphasis will come more on building ships with desirable emissions control power systems, since the availability and price of fuel will be driving overall costs.

That’s an interesting point. We will see the extent to which it influences the next generation or two of ship orders.

Sam Chambers July 27, 2022

Liners get a preview of alternative fuel costs – Splash247