The Getting to Zero Coalition and the Global Maritime Forum have issued a new report At a Crossroads: Annual Progress Report on Green Shipping Corridors 2025. Green shipping corridors are a very impactful way of moving toward zero emissions in the maritime area. They can coordinate many players by providing a specific attainable goal— zero emissions on a specific route for specific ship types. These corridors are independent of efforts by the EU to create incentives and penalties for carbon emissions and reductions, and of efforts by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to reach a consensus on rules and measures for intrnational ocean shipping. Many times they are organized by specific ports and specific ocean carriers. Often they try to focus efforts on supply chains for specific fuels at those ports.

I think these efforts are extremely important. They can show how to provide reasonably priced fuel supply chains and how to coordinate investors, ocean shipping players, and financial institutions as well as governments. These experiments need to be tried.

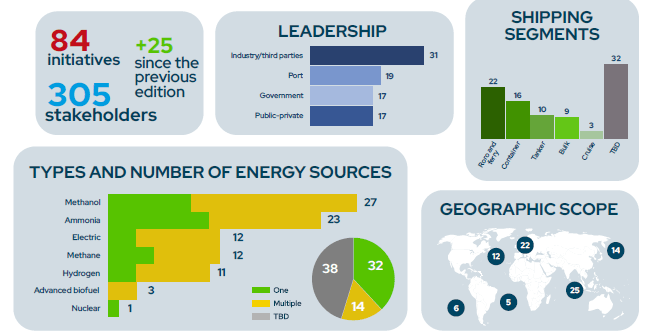

The report has been published since 2022, effectively the beginning of the green shipping corridors movement. Steady gains have been made, and today there are 84 initiatives catalogued, with 305 stakeholders. 25 more initiatives have been recorded.

Source: Annual Progress Report on Green Shipping Corridors, 2025.

An interesting section discussed progress at the four corridors that have reached the highest stage in the journey: the Realization stage. Three of them are short-sea routes in Europe. The longest runs bulkers from Australia to China and other Far East ports.

- Stockholm-Turku ferry, Finland to Sweden, biomethane;

- Vaasa-Umeå ferry, Finland to Sweden, biomethane;

- Australia-East Asia bulk carriers, iron ore, ammonia;

- Oslo-Rotterdam container ships, hydrogen.

I found it interesting that the three short routes fund the difference between green and dirty fuels by entering pooling agreements to sell credits to other shipping lines, under the EU policies. The long ammonia route alone is driven by private firms involved in the trade, to help them meet dramatically lower emissions goals, with fuel costs not funded but expected to drop to a reasonable level as the infrastructure is built out. China, Korea, and Japan all have goals for reduced emissions from shipping which the iron ore route will help with.

Four recommendations emerge from the report’s assessment of the green corridor potential and progress.

- Pursuing strategies to break the inertia and keep the momentum;

- Connecting cargo owner willingness to pay to the corridors;

- Taking an active stance at the IMO;

- Tapping into or replicating emerging national policy instruments.

Significant issues for now are:

- Delay of the IMO Net-Zero framework; participants may wait for more clarity.

- Will the cargo owner be willing to pay for green shipping on the corridor? The evidence so far is not good.

- Influencing public policies to support investment and regulation.

- Staying focused on truly green corridors that deploy zero-emission assets rather than fossil fuels, do it early, and iron out the kinks.

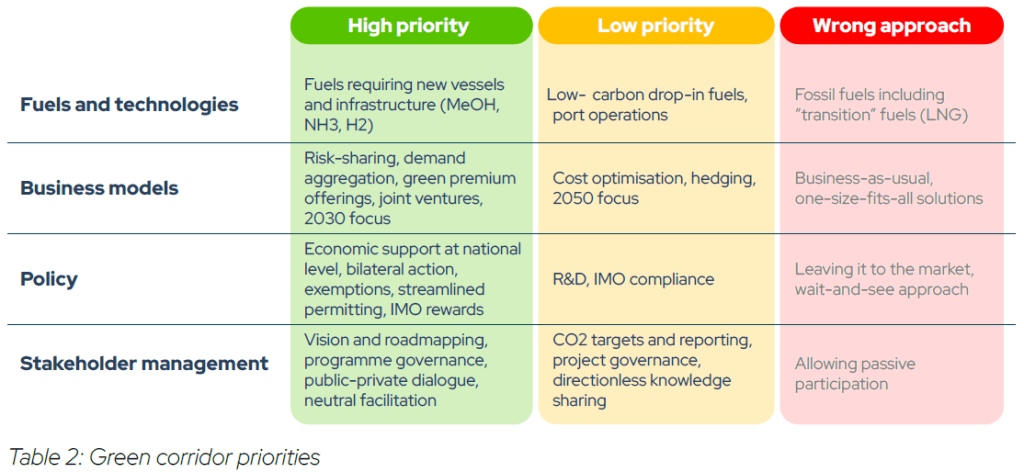

This chart shows the right and wrong approaches:

Source: Annual Progress Report on Green Shipping Corridors, 2025, page 25

The study is available in PDF at this link. It contains an Appendix listing all the current Green Corridors in the portfolio at present.

I was very happy to read this summary of the state of green corridor adoption. Keeping this movement going will play an important part in maritime decarbonization.

Gary Howard, Middle East correspondent November 27, 2025

https://www.seatrade-maritime.com/green-shipping/first-four-green-corridors-hit-realisation-stage